Happy Sunday,

COP26 kicked off today and for the next two weeks whether we like it or not, we are going to be inundated with climate news in all its doom, gloom and glory — all the jargon, the achievements, innovations and controversies.

I’m headed to Glasgow where I’ll be in the middle of all the action, giving you a seat at the table with a three-part COP26 Chief Brief of how our climate change journey is truly going! I’m guessing there will be a lot of disappointments, interspersed with a trickle of hope. The first of the gloomy stories broke a few minutes ago, with scientists saying the world is pretty much out of time to stop climate change. The earth has already warmed by more than 1.1C and current projections based on planned emission cuts over the next decade are for it to hit 2.7 degrees by the year 2100.

Next Sunday I’ll talk about the action in week 1 from the core ‘blue zone’ (access here is like winning the lottery I’m told) where I’m hosting Nature’s Newsroom where leaders gather to negotiate and make decisions. In week 2 of the climate talks I’ll bring you perspectives from the ‘innovation zone’ - where I’m hosting the Sustainable Innovation Forum and the Hydrogen summit — getting a front row seat to deep dive into the global private and NGO C-suite’s real action plans.

As the conversation becomes centred around the world’s 1.5-degree target (for at least two weeks) — here’s a cheat sheet for all the hot topics you’re going to hear about. More importantly, it is a cheat sheet to the women at the forefront of the climate conversation. Whether their roles, actions or sectors are controversial or celebrated, it’s a good reminder that in drawing out the plan for our future, women must be and are, very much a part of the fray.

The quick note

CO2

I doubt anyone has forgotten their chem class in school, or the periodic table (well the basic elements anyway), or the multitude of times we’ve heard it since — but just in case: CO2=Carbon Dioxide.

Why is it bad?

It’s not. Well, not if it doesn’t exceed naturally present levels (which it has). Like other greenhouse gases, CO2 absorbs radiation and prevents heat from escaping from our atmosphere. But high amounts of atmospheric CO2 collects and stores heat, disrupting weather patterns, causing global temperatures to increase and other climate changes (think melting glaciers, starving polar bears, fires, floods etc).

Net zero

It’s the target everyone spouts, and it means, offsetting all (I mean ALL) carbon production with renewable energy or carbon capture processes (scroll below).

Carbon emissions

This is the unit that measures the CO2 equivalent that may be released from a chosen human activity. The lower the CO2, the lower the impact the activity has on the environment.

Carbon footprint

This is a calculation of the sum of all emissions of CO2, which were induced by a person/entity’s activities in a given time frame. Usually, a carbon footprint is calculated for the duration of a year.

The longer note

What’s UNFCCC?

This is the United Nations entity tasked with supporting the global response to the threat of climate change. UNFCCC stands for United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

COP26 - what is it?

The COP is the supreme decision-making body of the Convention and meets annually. The Conference of the Parties 26th annual gathering is known as COP26 and is a critical summit for global climate action.

To have a chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees, the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report states global carbon emissions must be halved by 2030 and reach ‘net-zero’ by 2050. According to the IPCC, achieving this target is only possible if unprecedented action is taken now. COP26 is the first test of this ambition-raising function.

What is the Paris Agreement?

After more than two decades of diplomacy, the world finally agreed in 2015 that everyone had to act to save the planet. Adopted at COP21 in Paris the majority of the world’s nations committed to containing global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1.5 degrees (remember that target I mentioned above?).

What’s the Paris Rulebook?

In 2018’s COP24 in Katowice in Poland, countries gave themselves 3 years (i.e., 2021) to agree on the implementation guidelines for the Paris Agreement. Countries adopted the majority of the Paris Rulebook (aka the Katowice Climate Package), consisting of three core tenants: Plan, Implement, Review — but left (predictably) quite a few unresolved issues like Article 6 (e.g., carbon markets).

What’s Article 6?

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement sets out rules to strengthen the integrity of carbon markets to create a new global carbon offsetting mechanism. With developed countries being accused of double counting offsets, and the global south upset at potentially being hamstrung in their development — No one can agree on the finalised rules, and it isn’t likely a solution will be found in Glasgow either. What are the goals everyone’s disagreeing on?

To prevent all forms of double counting of mitigation toward the achievement of Paris Agreement temperature goals. (see carbon offset controversy below)

Facilitate high-quality mitigation across all sectors.

Ensure comprehensive reporting and transparency.

Meet COP’s leaders

The woman who led COP21 - The Paris Agreement

Christiana Figueres, was Executive Secretary of the (UNFCCC) from 2010-2016. She took over negotiations after a failed COP in Copenhagen in 2009. She led the build-up of COP from Cancun to finally the historical Paris Agreement. Christiana is still a very prominent face in every climate conversation (including COP26) and is currently the co-founder of Global Optimism, co-host of the podcast “Outrage & Optimism” and the co-author of the book, “The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis”. She is a member of the B Team, non-executive Board member of ACCIONA and Impossible Foods.

Patricia Espinosa of Mexico has been Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC since 2016, (when she took over from Christiana Figueres). Before her role at the UNFCCC, Patricia was Mexico’s Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2006 to 2012 and brings to her job saving the planet —more than 3 decades of experience in international relations, specialising in climate change, global governance, sustainable development, gender equality and protection of human rights.

What’s COP26’s measure of success?

One of the main ‘benchmarks for success’ in Glasgow is that as many governments as possible submit new nationally determined contributions (NDCs) - or simply put national plans for every COP member to get to net zero. When put together, these need to be ambitious enough to put the world on track for ‘well below’ 2 degrees, preferably 1.5. That critically means an agreement on Article 6 (which of course isn’t likely).

At COP21 (Paris, 2015) the NDCs submitted were weak — not even enough to get to ‘well below’ 2 degrees, never mind 1.5 degrees. In COP25 everyone walked away with no resolution. While there was hope that the new and more ambitious NDCs (submitted every five years) at Glasgow could get us there, that hope is ebbing. With the world’s biggest polluters China and Russia not even attending, everyone’s been busy tempering expectations in the past few days - from John Kerry to Boris Johnson.

And here’s why expectations aren’t as high as the UK Presidency would like: As of September 2021, 86 countries and the EU27 have submitted new or updated NDCs. Others like China and Japan have pledged new 2030 targets but haven’t submitted them officially. But 70 odd countries are yet to communicate new or updated targets. Others like Australia, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, Singapore, Switzerland and Vietnam – have submitted, but without raising ambition. Countries are also starting to hedge on 1.5 degrees, with some governments (including in Europe) talking about shifting focus to 1.6, or 1.7 degrees. Others are planning to say that 2022’s COP27 gathering (potentially in the pretty resort town of Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt) will be the next “final stand”.

Cutting through the jargon

(Or as Greta Thunberg likes to say.. all the “blah blah blah..”)

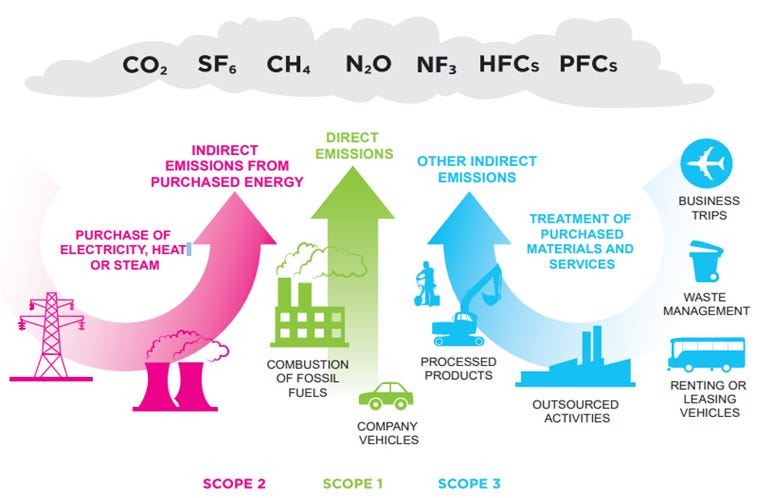

Scope 1, 2, 3 emissions

Scope 1: Fancy way to describe direct emissions from a company’s own sources (green arrow).

Scope 2 is simply the indirect emissions from the consumption of electricity, steam, heat or cooling that has been purchased (pink arrow).

Scope 3 are the most critical to address. These are indirect emissions not owned by the company but are linked to the company’s operations or supply chains (blue arrow).

Carbon Credits & Carbon Offsets

What’s carbon offsetting?

To get to net zero, we can all do our bit as individuals and organisations. For example — find ways to reduce our carbon footprint from our lighting and heating to the data centres that host business software, or business travel. But that usually isn’t enough (think Scope 3 emissions)! That’s when carbon offsets play a major role.

It essentially means negating or offsetting the same/equal amount of CO2 that we would release into the atmosphere. The offset is created by backing a renewable energy source or funding activities like planting trees. And when that isn’t enough to negate the CO2 we put into the air, we can buy carbon credits.

What’s a carbon credit?

Carbon credits are simply permits that are measurable, verifiable emission reductions from certified climate action projects which reduce, remove or avoid greenhouse gas emissions. Businesses buy these to meet emission targets — Carbon credits compensate for those emissions businesses haven’t yet eliminated. Once used they are permanently retired and cannot be reused.

High-quality carbon credits should adhere to a strict set of standards (though they don’t always). These can be checked to ensure they are registered with a third-party internationally-recognised verification standard, such as the Gold Standard, Verra's Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), Social Carbon and Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards (CCBS), or standards verified by the UNFCCC.

Why the controversy?

The offset market valued at an estimated $100 billion by 2030 (according to former Bank of England governor Mark Carney) and is often described as the Wild Wild West (even by supporters!). Why? Because a lack of agreement on Article 6 means there are no rules and regulations to govern the market.

First up -- the dreaded double counting! It’s cheaper for two or more countries to get to their emissions targets together than going it alone. But the rules are so lax that it could actually lead to greater emissions. This is at the heart of the problem. A country selling a carbon credit may claim the underlying emissions reduction for itself, while the country buying the credit also claims the same exact reduction.

Here’s the other problem with the offset market — oversight. The practice’s effectiveness is questionable if you go by research that indicates the green projects chosen to earn carbon credits have a low likelihood that emission reductions are additional and are not over-estimated. For e.g.: The forest protection carbon offsetting market used by major airlines for claims of carbon-neutral flying faces a significant credibility problem.

That makes activists believe carbon offsets are simply a way to pay lip service to the net zero target, without making the difficult transition to eliminate emissions themselves.

Carbon credit+offset leaders to know:

Janaina Dallan is a Partner at Carbonext, based in Brazil. She is responsible for the development of climate change projects with potential for generating carbon credits in the regulated market

Sanchali Pal is CEO and founder of start-up Joro, which helps individuals track their carbon footprint. She tracked her carbon footprint for several years on a spreadsheet before realising she needed to build a tool to make the process easier for herself and others concerned about climate change. Sequoia Capital has bought into her story hook line and sinker.

Carbon Capture and Storage

What is it?

You’re going to hear someone very woke (or someone who’s smartly investing) throw the acronym CCS around at dinner sometime soon. What they’re talking about is Carbon Capture and Storage — the process of containing CO2 produced by burning fossil fuels (or other carbon-producing processes) and storing it in a way that it can’t get into the atmosphere.

Why everyone’s talking about it & why it’s controversial?

The global market for CCS was estimated at US$2.8 Billion 2020 and is projected to grow at a whopping 9.9% and reach a revised US$4.9 Billion by 2026. Humans emit around 35 billion tons of greenhouse gases a year. To keep temperature increases below 2 degrees will require the removal of between 10-20 billion tonnes of CO2 every year until 2100. While researchers agree CCS is not a silver bullet to our emissions problem, it is one of the tools that can be used.

Here’s the controversy part — the overwhelming majority of the world's 89 CCS projects currently in operation, being built or in advanced stages of development are operated by oil, gas and coal companies (the dirty trio). The CO2 they remove isn’t with the motivation to reduce emissions. It is instead re-injected into oil fields that are nearly depleted to help squeeze out 30-60% more oil than with normal methods. The process is known as “enhanced oil recovery” — not exactly a move toward other cleaner energies or in the spirit of climate protection.

CCS leader to know:

Edda Aradottir, is the CEO of Carbfix in Iceland. It is the world’s first direct air capture and storage concept. Carbfix captures CO2 which is injected into basaltic rock-formations to be permanently turned into stone within two years. Its Orca plant (its name derived from the Icelandic word for energy) went live in September —and its creators and operators, Swiss firm Climeworks and Carbfix, say it's the world's largest.

Circular economy

What is it?

It is the much talked about model of production and consumption that aims to avoid unnecessary emissions. A circular economy involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible.

Circular Scandal

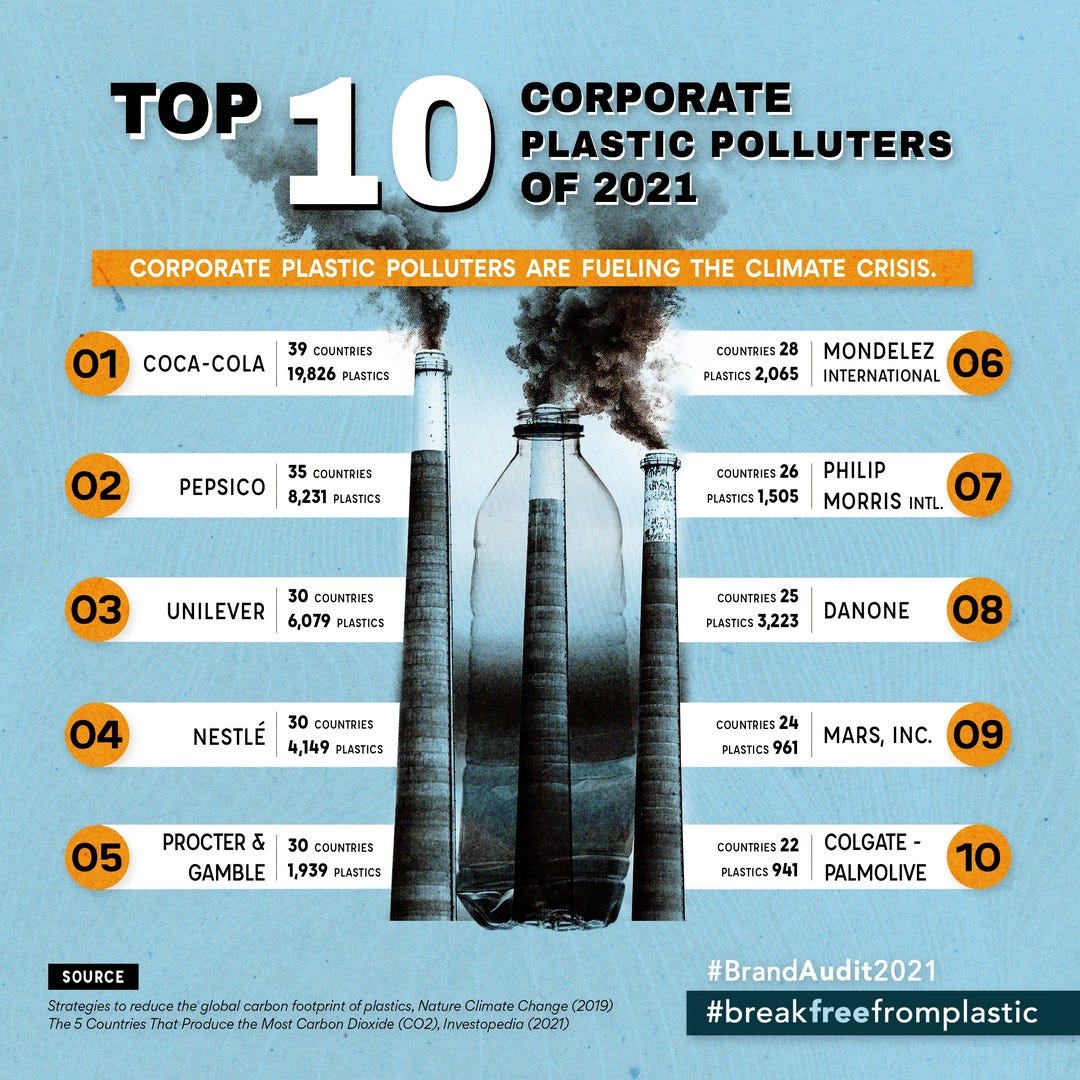

It’s got to be more than embarrassing to be headed into COP26 to talk about net zero targets, sponsor sessions and events (I’m looking’ at you Unilever!), only to be named corporate plastic polluter of the year, just a few days from the big show!

Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Unilever were found to be the world’s biggest polluters of plastic this year. They were followed in fourth and fifth place by Nestlé and Procter & Gamble. Coca-Cola though, managed to contribute more pollution than both PepsiCo and Unilever combined. The irony of Unilever being a principal sponsor of COP26 isn’t lost on us observers too. These corporates are also the biggest names in talking the sustainability and circularity talk. But something, somewhere is obviously not working.

Over 11,000 volunteers in 45 countries across 6 continents cleaned beaches and parks for the annual audit for ‘Break free from Plastic’ (which began in 2018) identifies the worst culprits of plastic pollution. This is an environmental alliance that includes Greenpeace, Gaia, and Zero Waste.

What is important now is action that goes beyond just naming and shaming (which is of course essential to stop the greenwashing rhetoric) and find a committed strategy that allows for the innovation and implementation of a successful solution to the problem. In addition to ocean conservation issues and plastic’s lack of biodegradability, did you know 99% of plastic is made using fossil fuels? And did you know the production and recycling of just 1 tonne of plastic, emits almost 5 tonnes of CO2? Those numbers don’t paint a great picture for the net zero target we keep hearing about.

So, what can you and your organisation do to NOT make this list next year? Maybe talk to the women below!

Plastic pollution experts to know

Nicky Davies is the Executive Director of the Plastic Solutions Fund, an international group of funders who have joined forces to turn the tide on plastic pollution in the air, land, rivers and oceans.

Jacqueline Savitz is the Chief Policy Officer of Oceana, the largest international advocacy organisation dedicated solely to ocean conservation. She oversees all of Oceana’s work in North America and directs the organisation’s new international campaign to reduce the amount of single-use plastic being produced at the source.

I hope the cheat sheet was helpful, and that you find the women paving the way inspiring. Drop a comment below or get in touch if you want to learn something specific from COP26.

Are you planning to be there? I’d love to say hi!