Remember the all-women Blue Origin flight? The world cheered, it booed—and then moved on.

But here’s why we shouldn’t. The flight made headlines. But behind the sparkle was something far more serious: a PR gloss over a troubling purge of real women leaders in space, science, and security. This isn’t just about optics—it’s a geopolitical pivot with global consequences.

This edition of The Chief Brief unpacks where real opportunity and leadership in space is quietly rising—often far from the cameras, and increasingly, far from the U.S.

Glam Up, Blast Off, and Don’t Ask Questions

What Blue Origin’s ‘historic’ flight Wasn’t

1. It wasn’t a “crew.”

It was a suborbital tourism flight. Eleven minutes. No mission. No operations. No training beyond passenger prep. If you’re not operational, you’re not crew.

2. It wasn’t “the first.”

Valentina Tereshkova went to space alone in 1963. A textile worker from the USSR. Three days in orbit. No glam squad. Just grit.

3. It wasn’t astronaut work.

It skimmed the Kármán line. Becoming an astronaut takes years of rejection, training, and technical mastery. This was not that. Though the definition of what is an astronaut, is getting blurred for the sake of those expensive rides by private companies.

Watch this NASA video for the full reality check of what it takes to go to real space.

What we got:

A pre-wedding PR spectacle with glam squads and gift bags. The press lapped it up. Gayle King cheered. Katy Perry cried. Lauren Sánchez and her entourage gushed about getting “glam” before take-off. Compare that to the headlines mocking real astronaut Sunita Williams for her appearance after returning from being stuck for months on the International Space Station (ISS).

What we lost:

Public trust. Scientific seriousness. And the chance to centre actual women in science.

As the champagne was being uncorked mid-air, actual women leaders in U.S. space and security were being fired.

• NASA DEI lead Neela Rajendra? Gone.

• Col. Susannah Meyers, Space Force’s Greenland base commander? Fired.

• Dr. Kate Calvin, NASA’s chief scientist and climate advisor? Ousted.

• Janet Petro, NASA’s acting administrator? Under fire, and reportedly being replaced by billionaire Jared Isaacman—who bought his way into two SpaceX missions.

This past fortnight came the gut punch for many (though international folks in anything to do with Women Peace & Security (WPS) had a gut feeling this was coming):

Pete Hegseth, overseeing America’s defence, declared war on WPS — ironically a Trump-era bipartisan law proposed by Ivanka Trump.

He wrote on X:

“WPS is yet another woke divisive/social justice/Biden initiative that overburdens our commanders and troops… GOOD RIDDANCE WPS!”

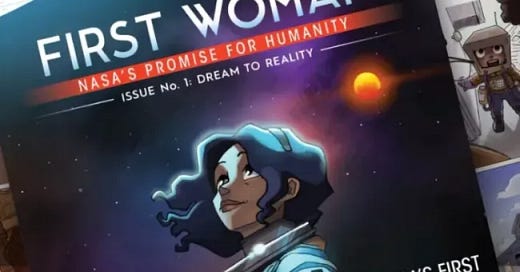

Just days before the ‘girlboss launch’ — in February, NASA scrubbed its own “First Woman” comic series from the web. Callie Rodriguez—the fictional Latina astronaut created to inspire girls —gone. No statement.

Even NASA’s “Women in Leadership” content? Removed.

Let’s be clear. The purge began even before the formal Trump inauguration. One of the first to be ousted was Shelly O’Neill Stoneman, Lockheed Martin’s SVP of government affairs. Right wing media company Breitbart reported she posted progressive political opinions online, and in a snap Shelly was quietly exited from the company that depends on the U.S. Department of Defence (DoD) for more than 70% of its revenues.

Lockheed, unsurprisingly, is sticking with the storyline that she resigned for “personal reasons.” You can read into that, what you will.

The message from Washington is clear:

We’ll celebrate women in space—as long as they’re not running it.

Where the Real Money Is Going?

On May 2nd this year, the White House's President’s budget for Fiscal Year 2026 indicated NASA's topline funding will potentially be cut by 24% and its science budget by 47%. Meanwhile, it’s been announced the U.S. government is pumping its Space money elsewhere

• $6 billion is going to Elon Musk/SpaceX.

• $2.3 billion to Jeff Bezos/Blue Origin.

The United States is gutting science and handing over exploration to the world’s richest men.

Meanwhile, the Artemis program—the mission to deep space and the Moon —is on shaky ground.

So What Is the Real Signal?

To young women watching:

• Lead missions, solve climate challenges, run space centres → Get fired.

• Marry rich, trend on Oprah’s WhatsApp → Get a glam team and go to “space.”

Blue Origin wasn’t about inclusion. It was a distraction.

As Olivia Munn quipped, if anything went wrong, we’d be seeing if eyelash glue could save the day. Considering what has followed since that “historic flight”, we might need to keep that eyelash glue on standby.

Spoiler: The World Has Its Own Ideas

Before we start the hand-wringing on global DEI backlash —grab a cuppa and breathe.

The U.S. may be backpedalling on its self-created DEI acronym, but the rest of the world is quietly building inclusive space programs—with no hashtags, no applause. DEI afterall means very different things to different parts of the world.

Of course, countries across the world are wrestling with low numbers of women in space science—but (and it’s a meaningful but) the shift is palpable. Reassuringly, it seems The 1967 Outer Space Treaty and wording are still the global standard:

Space must benefit all of humankind.

That includes women.

Breaking Down the Numbers

Who’s Actually in the Space Game?

Myth #1: It’s just the U.S., Russia, and China.

Yes, they lead in launch power—but the space race is far more crowded. The most established programs:

United States (NASA/United States Space Force or USSF)

Russia (Roscosmos)

European Space Agency (ESA) – Members: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK.

China (China National Space Administration or CNSA)

India (Indian Space Research Organisation or ISRO)

Japan (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency or JAXA)

Then there are the emerging players: Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, South Korea, Israel, Iran, Turkey, UAE, Rwanda, and Kenya among others.

Myth #2: DEI ruined the talent pool

Women are still underrepresented across the board. The idea that DEI led to a glut of unqualified women in space is simply false—though publicity and PR might suggest otherwise. And of course there will be a few lemons in the mix. There always are. That’s not exclusive to women.

Space research feeds so much of the innovation we need to solve problems here on earth and UNOOSA’s 2024 Space4Women study — the largest of its kind (and yes, there is a UN agency dedicated to all things outer space!) collected data from 53 public-sector agencies across 46 countries to find how reflective the sector was, of the world and its inhabitants.

None of their data points to a ruined talent pool. Rather, the missed opportunity for recruiting talent.

(China no surprise, didn’t participate - they aren’t exactly the data sharing types.).

The Findings?

• Women = 30% of the global space workforce

• 24% of managers

• 21% of leadership

• 19% of board members

• Under 20% of technical roles

• 11% of astronauts

The result: a very limited understanding of female physiology and experience in space. (Why does that matter? Let us save that for another edition.)

Yet, 25% of countries surveyed had 50% or more women in their agencies.

Europe and North America? All Talk

According to the OECD’s Space Economy in Figures report (2019)

In Europe and North America women account for:

Slightly more than 20% of space manufacturing employment

Approximate 10-15% of aerospace engineers

In Europe, juxtaposed to the United States - the momentum for an inclusive space is building, with a new generation of astronauts being developed.

ESA’s new cohort includes Sophie Adenot (France), Rosemary Coogan (UK), Anthea Comellini (Italy), Sara García Alonso (Spain), Nicola Winter (Germany), and others.

Building on names like Samantha Cristoforetti (Italy), Claudie Haigneré (France), Helen Sharman (UK)

The real story?

Africa and Asia are quietly outperforming.

Africa: Quiet Leadership

Despite no launch capabilities on the continent, The eye-opening data?

22 out of 54 African countries are involved in space activities.

Around a quarter of African countries surveyed, have gender parity in workforce and leadership.

The challenge? Not just funding. It’s lack of visibility, role models, and sector awareness.

What they do have? Science capabilities.

UAE: Regional Benchmark

• 50.7% of staff at UAE Space Agency = women

• 42% Emirati women at Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre

• 70% of astronaut program = women

• 80% of Mars Hope science team = women

Fun fact: In 2021, Nora Al Matrooshi became the UAE’s first female astronaut

Saudi Arabia: Reform in Motion

• Women = 28% of Saudi Space Agency

• The Saudi ‘Vision 2030’ is pushing more women into STEM leadership, the target? 30%.

• The Saudi Space Agency’s BioGravity research team? Women-led. Dr. Wijdan Al-Ahmadi, Dr. Ibtihaj Al Sharif, Dr. Deema Kamal Sabir, and Dr. Hadeel Ahmed AlSufyani are leading the microgravity research.

Fun fact: Rayyanah Barnawi became the first Saudi woman in space in 2023

India: Eyes on the moon

India aims to establish its own modular space station by the mid-2030s and land an astronaut on the Moon by 2040.

It is a major satellite launch provider for other nations

Women make up 17.64% of staff in India’s Department of Space (DOS): 1,163 in scientific and technical roles, 1,259 in administrative.

(The DOS is India’s national space agency, responsible for research, development, and execution of the country’s space programme. It oversees ISRO, satellite development, launch vehicles, and space science missions.)

Fun fact

• Ritu Karidhal, Nidhi Porwal, Kalpana Kalahasti: key architects of Chandrayaan missions

• Reema Ghosh built the lunar rover Pragyan

• Dr. Vandana Singh & Annapurni Subramaniam are leading inclusive science policy

China: Relentless, Strategic

No public data, gender or otherwise but China launched six spaceflights in 2025 alone.

Wang Yaping became the first Chinese woman to conduct a spacewalk.

Wang Haoze, China’s first female space engineer, now works aboard the Tiangong space station.

Call a spade a spade, when it comes to China - there are no distractions. Just execution.

These are just examples of much of the world not prioritising “DEI” as a headline agenda. Instead, the focus is on building long-term capacity —quietly aligning their science and space programmes with national goals and broader citizen needs.

Beyond the Noise: The Real Test is Still Ahead

For now, the real work of U.S. space leadership is quietly advancing inside NASA—under political and fiscal pressure and global scrutiny.

International Space Station veterans, scientists like Jennifer Buchli and Meghan Everett continue to quietly drive U.S. orbital research—so far, untouched by Trump’s political machine.

Take Artemis II. It’s more than a ‘fly me to the moon’ lyric. It’s a litmus test for whether the United States can still deliver complex, multi-year missions in a fractured, short-attention-span political environment.

The crew—Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen (the tariff effect hasn’t been seen here yet) —will travel 8,889 km beyond the Moon and back. This will be NASA’s first crewed deep space mission in over 50 years. The launch is now pushed to no earlier than February 2026, following recent reviews of the spacecraft’s heat shield and life support systems.

All the major hardware—the SLS rocket (built by Boeing and Northrop Grumman) and the Orion spacecraft (Lockheed Martin)—has arrived at Kennedy Space Center for final integration. Crew training is well underway.

But the risks are now plain. The current U.S. administration has yet to publicly back Artemis, but the budget proposal for 2026 would slash NASA’s science and education funding—potentially pulling the rug out from under the entire Artemis program. Back in December, Elon Musk dismissed Artemis as “jobs-maximizing,” and the whispers in D.C. and industry circles point to a possible pivot to Mars, and a deprioritization of the Moon mission entirely.

If Artemis fails—so does U.S. credibility.

If the U.S. falters now—whether by bleeding talent standing on the hill that is DEI, wavering on purpose, or simply losing momentum— the fallout won’t be domestic alone. A budget rollback or policy reversal would destabilize missions and partnerships that involve some of the U.S.’s closest allies: the European Space Agency, Canada and Japan.

But folks in the west must remember — others are on the move. China’s lunar ambitions are no longer aspirational—they’re advancing. And India is getting ready to send humans to space.

Artemis is no longer just about NASA. NASA is no longer about a dream to explore where no man has gone before. It’s a global signal of whether the United States still has the will—and the steadiness—to lead.

That window is still open. But not for long.

Space Trivia for your next party

Christina Koch (Artemis 2 astronaut, if it ever launches) holds the NASA record for longest single spaceflight by a woman: 328 days. Only Scott Kelly did more—340.

The American with the most time in space? Peggy Whitson. She holds the NASA record for total days in space and shares the all-time spacewalk record with a man: 10.

In 1983, the legendary Sally Ride had to explain periods to NASA engineers. They asked if she needed 100 tampons for a 7-day mission.

Since the dawn of the space age: There have been 35,000–40,000 rockets launched (including suborbital and orbital). There have been more than 6,500 Orbital rocket launches.

There are approximately 11,330 active satellites orbiting Earth

A module called Kibo, on the International Space Station gives astronauts a VIP space experience.

NASA’s first interplanetary CubeSats, Mars Cube One (MarCO), were named after two Pixar characters WALL-E and EVE

Movers & Shakers

🇮🇳 Aarthi Subramanian is now President and COO of Tata Consultancy Services, making her the first woman COO in India’s $245 billion IT sector. She’ll oversee operations at the $30B tech giant—marking a rare moment of gender-firsts in a traditionally male-dominated industry.

🇧🇩 Jahrat Adib Chowdhury has been named Deputy CEO of Banglalink, Bangladesh’s third-largest mobile operator. Formerly its Chief Legal Officer and Company Secretary, her elevation signals a shift in leadership pipelines across South Asia’s digital sectors.

🇿🇦 Liyema Letlaka steps in as Acting CEO of the Southern African Endurance Series (SAES), becoming a key figure in South African motorsports. Founded in 2021, SAES runs the SA GT National Championship—one of the country’s fastest-growing sporting platforms.

🇬🇧 Stella David has been confirmed as the permanent CEO of FTSE 100-listed Entain plc, owner of gambling giants Ladbrokes, Coral, and PartyPoker. A boardroom mainstay at Entain, she now takes the reins amid efforts to steady the company after a period of turbulence and leadership shake-ups.

🇬🇧 Monica Collings is the new Chair of POWERful Women, the U.K. industry initiative pushing for 40% female leadership in energy by 2030. Previously CEO of So Energy—and the only woman to lead a U.K. energy supplier at the time—she brings frontline credibility to the push for structural change.